Campus Building Profile: Mueller House and The Lodge

This is the third story in a series exploring and celebrating the history of the iconic buildings on Chatham’s campus. The original Berry Hall and the libraries were covered in previous installments.

The expanse of land near the northern edge of Allegheny County was mostly undeveloped wilderness, and it was there that Sebastian Mueller sought refuge for himself and his wife. He had a farmhouse built for them and a stable built for horses. Then Mueller brought others, and the farm became a retreat where factory workers could escape the soot-stained streets of Pittsburgh and soak in the clean calm of nature.

It was this way for decades on Eden Hall Farm, even long after Mueller died in 1938, 26 years after he bought the property. The factory women stopped coming as they found other places to vacation. By the end of the century, the farm became unsustainable, and the land and buildings languished in the mid-2000s as funds dwindled and visitors disappeared.

The Eden Hall Foundation, the nonprofit that oversaw the farm in that era, in 2008 gifted the land to Chatham University and the nearby Pine Richland School District. The University built its Eden Hall Campus, focusing on sustainability and the environmentalism with new structures, solar panels, and a residence hall.

But two structures – Mueller’s farmhouse and the lodge built in the 1950s for guests – still stand as the most salient reminders of what Eden Hall Farm once was.

Mueller Comes to Pittsburgh

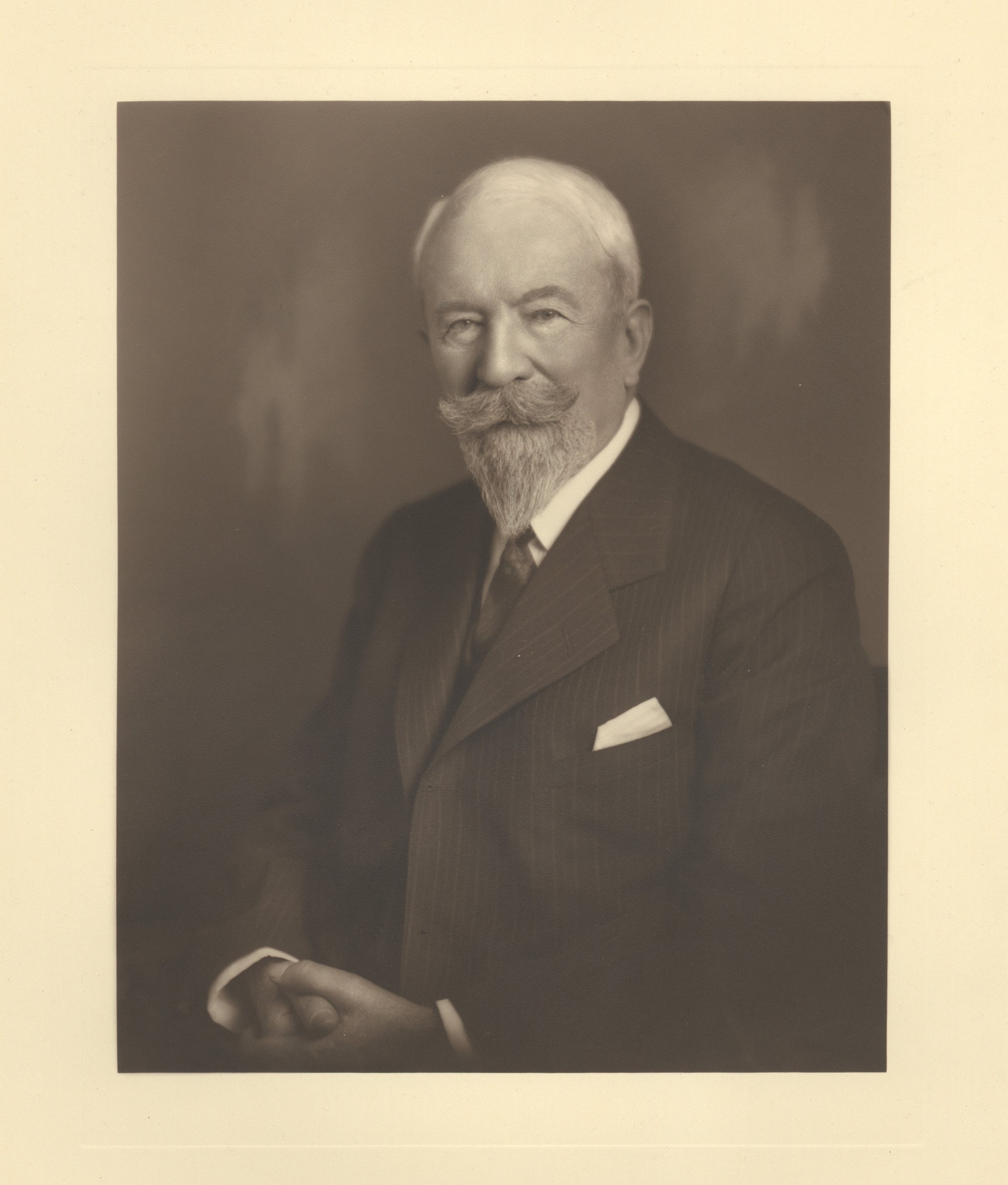

Sebastian Mueller poses for a portrait. (Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

Mueller was born in Bavaria (modern-day Germany) in 1860. He was raised by his aunt after the death of his mother in 1869. At age 24, he moved to Pittsburgh, and he began to work for his cousin, Henry Heinz, at the H.J. Heinz Company. Beginning as a laborer for the growing food processing business, he quickly ascended the ranks.

After marrying Henry’s sister, Elizabeth, in 1888, the two men became even closer. Sometimes, when his cousin was away, Mueller assumed his role overseeing the company. As the business grew into the iconic brand it is today, the men and their families became wealthy. Mueller grew a large, well-groomed goatee, which he would maintain for the rest of his life.

Even as Mueller gained wealth and prestige, tragedies defined his family life. In 1892, his daughters, three-month-old Elsa and one-year-old Alma, died after contracting diphtheria. The Muellers’ only son, Stanford, was born one year after the girls’ passing. He died from scarlet fever at the age of 18.

Eden Hall is Born

The death of his son led Mueller to return to Germany, where he recuperated at a spa in Wiesbaden. Robert Isenberg, in his slim 2017 book “A Brighter, Healthier Tomorrow: The Story of Eden Hall Campus,” compares this trip to the rejuvenation that people would experience when they visited what would become the 450-acre Eden Hall Farm, which Mueller bought in 1912 as a summer estate. A Craftsman-style home and a horse stable were built on the property.

As he reached the end of his life, Mueller invited Heinz employees, particularly female workers, who referred to themselves as “Heinz girls,” to Eden Hall for retreats. In an age where many working people spent their summers squeezed into the cramped rowhomes of industrial Pittsburgh, Eden Hall was one of the most expansive green spaces to which these working women could have easy access. Heinz employees could visit for free on a rotating basis.

Mueller stands next to a group of Eden Hall guests. (Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

After Mueller’s death in 1938, Eden Hall became the site of a wellness retreat and convalescent home for the working women of Heinz, in accordance with Mueller’s wishes. The trustees of Eden Hall commissioned the construction of the guest lodge, the swimming pool, and the bowling alley, which remain on the property today. A tennis court, patio, and lily pond were also created, and a permanent staff of cooks and groundskeepers worked on the site.

The Lodge at Eden Hall. (Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

Activities on the Farm

Photos and other materials in the Chatham University Archives and Special Collections give a sense of the pace of life at Eden Hall in the mid-1900s. A one-page, hardbound guide – it looks like a small restaurant menu – briefly lays out the lodge rules, mealtimes, and transportation for church services. Guests were expected to make their own beds.

Women relax and play shuffleboard at Eden Hall’s Lodge. (Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

A paperback booklet for guests, now stored in Chatham’s Archives and Special Collections, gives a short history of the farm and its “advantages.”

“Situated at the extreme northern end of Allegheny County, among Western Pennsylvania’s rolling hills, Eden Hall Farm covers an expanse of over four hundred acres,” it reads. “For those, who desire to enjoy the fresh air and sunshine of the summertime, the farm offers untold advantages.”

Among them: a “competent staff will prepare meals that will satisfy the most robust appetite;” “unlimited” opportunities for outdoor exercise and recreation; “facilities for outdoor sports such as swimming, roller skating, tennis, volley ball, mushball, archery, etc.;” and indoor “amusements” like ping pong and shuffle board during inclement weather.

“After a day spent actively indulging in such activities, the evening brings a welcomed opportunity to idle away a few pleasant hours on the cool porches under friendly trees,” the pamphlet promises.

The Buildings Today

Mueller’s Craftsman-style home still stands today. The University now simply calls it “Mueller House.” It retains many of its old charms; it takes little imagination to picture the women of Heinz gathered in the solarium that wraps around the home, watching the sun rise over fresh coffee. Staff for Chatham’s Center for Regional Agriculture, Food, and Transformation (CRAFT) have offices in the building.

Inside, past and present fold together. As soon as one steps through the main door, they’ll notice the original hardwood floors, a 1950s-era television, and modern appliances for the Chatham employees who work in the offices on the second floor. The ground floor still largely resembles a home.

A two-lane duckpin bowling alley still sits in the Lodge’s basement. (Mick Stinelli)

The Lodge, which was constructed to house Heinz girls and other guests when the farm opened as a retreat in 1951, also mostly houses University offices now. It was initially known as the Elsalma Lodge, its moniker a portmanteau of Mueller’s daughters’ names. This is where the Elsalma Fields organic garden on the campus takes its title.

The building exterior maintains its midcentury modern cool. On the second floor, the guest rooms have been turned into modern office spaces. The first floor consists of offices and a large conference room; at the far end, there is still a lounge area with a large piano. Portraits of Mueller and newspaper articles about the farm line the halls.

The Lodge’s basement is still largely occupied by two duckpin bowling lanes, but players will have to keep score by hand (they may also want to avoid smoking cigarettes, despite the built-in ashtrays).

A woman looks at Mueller’s profile, engraved in the back of a plaque dedicating The Lodge to his memory. (Chatham University Archives and Special Collections)

Just outside the Lodge sits the lily pond, where, engraved into a wrought-iron plaque, there is a dedication to Sebastian Mueller, “the man who made it possible.”

“During his life, his generosity aided and assisted many women of H.J. Heinz Company,” it reads. “At his death, he left this estate for their enjoyment and benefit.” Many more people have had the pleasure of visiting Eden Hall since it became part of Chatham, and its sustainability programs are ensuring it will be enjoyed for generations to come.

Mick Stinelli is a Writer and Digital Content Specialist at Chatham University. His writing has previously appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and 90.5 WESA, and he has a B.A. in Broadcast Production and Media Management from Point Park University. Mick, a native of western Pennsylvania, spends his free time watching movies and playing music.