A Chatham Professor Won a Top Prize for her Book on Toni Morrison

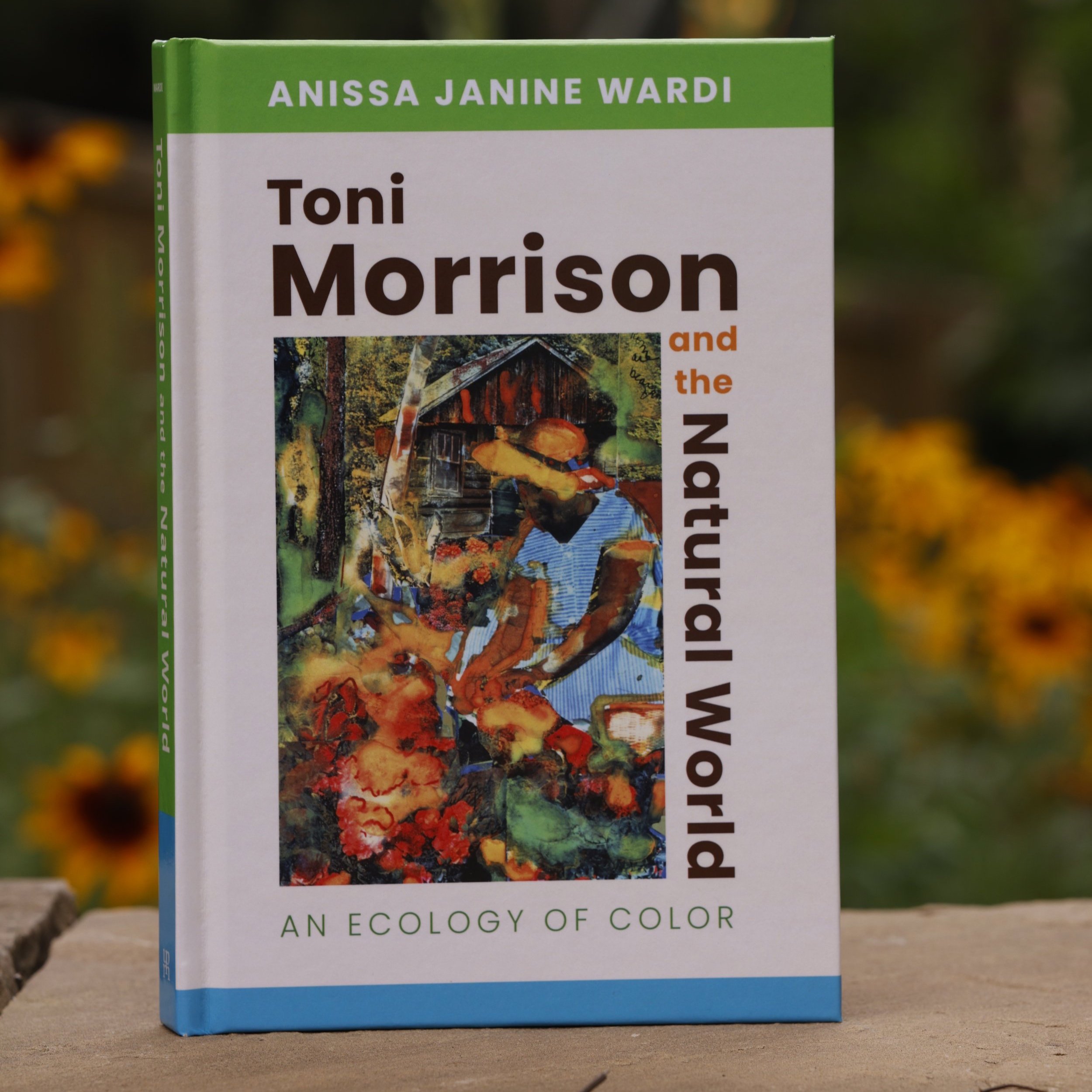

Professor of English Anissa Wardi’s “Toni Morrison and the Natural World: An Ecology of Color” won a Toni Morrison Society Book Prize this year. (Malcolm Kurtz)

Anissa Wardi first read Toni Morrison in college, where she was introduced to her novel “Song of Solomon” and wrote an undergraduate thesis on the legendary African American writer.

“Once I read that first novel, I devoured her work,” Wardi said. “She was the person I really wanted to study.”

It wasn’t until more than 25 years later that Wardi, now a professor of English at Chatham University, got to publish her first book on Morrison.

That book, “Toni Morrison and the Natural World: An Ecology of Color,” published in 2021 by University Press of Mississippi, this year won the Toni Morrison Society Book Prize for Best Single Authored Book 2019-2022, one of the highest honors out there for a Morrison scholar like Wardi.

She was in the Siesta Keys when she heard she won. “I was so filled with gratitude, but I was also so stunned—it wasn’t something I’d hoped would happen. It wasn’t something I aspired to.”

Wardi added that it was the greatest honor of her career to be recognized by Morrison scholars she has long admired.

After joining Chatham as a faculty member in 1996, Wardi designed and began teaching a course on African American literature. As she pursued her Ph.D., she brought aspects of ecocriticism—the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment—into her work.

“I think bringing an ecocritical approach to African American-authored texts is important, because, on one hand, it allows for newer interpretations of these works, but it also helps to redefine what we consider the canon of American environmental literature.”

That tradition, Wardi said, has long been dominated by white, male writers, such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, although she also noted the impact of Chatham’s most famous alumna, the environmentalist writer Rachel Carson.

Wardi’s teaching at Chatham has included courses on the Harlem Renaissance, August Wilson, and a Toni Morrison seminar. (Malcolm Kurtz)

Before publishing her Morrison book in 2021, Wardi spent her time at Chatham teaching courses and writing journal articles on ecocriticism in African American literature, including the book “Water and African American Memory: An Ecocritical Perspective” (University of Florida Press).

The more she taught and wrote, the more she felt confident in taking a look at Morrison’s 11 novels through an environmental dimension, such as how her writing connects the movement of plants and agricultural knowledge to the transatlantic slave trade.

“I just got excited about pulling it all together,” Wardi said. “Morrison was filling in the gaps of our national memory and showing us a kind of salvation people found in the land.”

She referenced the character Paul D, from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Beloved,” and his relationship to trees, particularly the one he nicknamed “Brother,” which sat upon the plantation where Paul D was once enslaved.

“I think, in moments like these, Morrison invites readers to recognize this deep sense of entanglement of the human to the nonhuman spheres, but also to see nature as a balm or salve in a system where social landscapes can be so oppressive,” Wardi said.

“Morrison, her poetic vision in her writing, I’d never read a novelist like her before,” she said. “I still haven’t. I think she is masterful, in terms of storytelling techniques, and she sheds light on stories we have yet to hear.”

A longtime fan, Wardi said she still gets excited discussing Morrison’s novels with students at Chatham, and she believes the writer’s work is more needed now than ever.

“Sometimes our discussion around issues of race can be simplistic, driven by social media discourse,” she said. “For us to really understand where we are, I strongly suggest people read some of these writers who have been grappling with some of these issues for decades now.”

A Bachelor of English degree at Chatham gives students the opportunity to immerse themselves in literature from the United States, Britain, and all over the world. Learn more at chatham.edu.