Can Emojis Make Coworkers Feel Closer to Each Other?

Monica Riordan was on a hot streak last month. She was promoted and became a full professor at Chatham University just after she published a research article in a major academic journal.

She wanted to share her excitement with her friends and family.

“I’ve actually been using that GIF of DJ Khaled going, ‘All I do is win, win, win, no matter what,’” she said, adding with a laugh: “I know this sounds obnoxious.”

If anyone knows the various ways GIFs—the repetitive moving images which are ubiquitous on social media—can be interpreted, it’s Riordan, whose research covers how people communicate their emotions in “cue-deprived environments,” such as text messages or e-mail.

Her most recent study, “Beneficial outcomes of (appropriate) nonverbal displays of negative affect in virtual teams,” will appear in the May 2024 issue of Computers in Human Behavior, a peer-reviewed journal.

In it, Riordan builds on her previous studies on emojis, one of which investigated the emotions stirred up by non-face emojis: a tree, food, the party popper, and others. Another paper examined how teams’ perceptions of their leaders were affected by higher-ups’ emoji use.

The new study (co-authored with Bar-Ilan University lecturer Ella Glikson) looks at whether using emojis in digital workplace communications improves the perceived closeness of a team.

“We found that people actually do believe that a team is closer when they do express emotions to each other,” she said. “Not only do they believe the team is closer and more free to express themselves to each other, but they actually want to be part of a team that does that.”

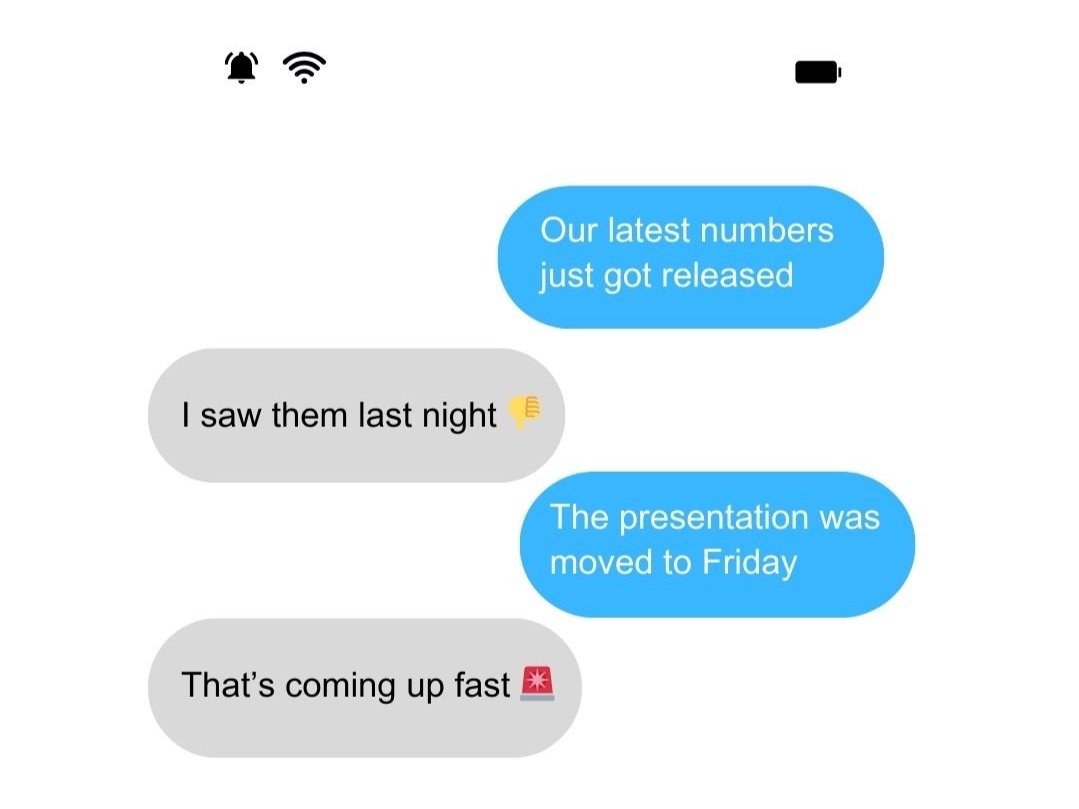

An image in the appendix of Riordan’s research paper shows how emojis were used to convey different emotions in text-based Microsoft Teams conversations. (Courtesy of Monica Riordan)

In some ways, this was surprising to Riordan, given some people’s concern that expressing their emotions—especially negative or unpleasant emotions—at work could seem unprofessional.

But what she found was that people felt better knowing where they stood in their relationships with their colleagues.

“These digital nonverbal cues, like punctuation and emoji… seem to be the appropriate way of conveying your emotion that doesn’t turn people off and gives enough information to understand where you are in your relationship with this person,” Riordan said during an interview at her office in March.

“It gives them clues about how to modify their behavior in that context to fix the relationship, as much as possible.”

The idea for the article came in part from Riordan’s own experience messaging colleagues and students amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“During the pandemic, a lot of my communication with students became online,” Riordan said. “We had online discussion boards. They were emailing me. I enabled them to text with me using Microsoft Teams, and a lot of the research work I was doing started to happen within Microsoft Teams.”

She started to see miscommunications pop up; for instance, if a colleague didn’t finish a project by a set date, Riordan puzzled over how she could express her genuine disappointment without antagonizing her coworker.

Tone and intention can be difficult to express, and harder to interpret, in writing alone. “You would have these conversations about, well, how do you know if this person is really being a jerk to you or is just overwhelmed?” she said.

Riordan said there’s still more to these types of digital communications she wants to understand. How does gender or power affect the online dynamic between coworkers? How do you effectively apologize to a colleague without overdoing or underdoing it?

But for now, she’s relishing the wins, one GIF at a time.

Read about more Chatham faculty research and explore opportunities for graduate student psychology research at chatham.edu.