Can Electric Fields Make Chemical Reactions More Sustainable?

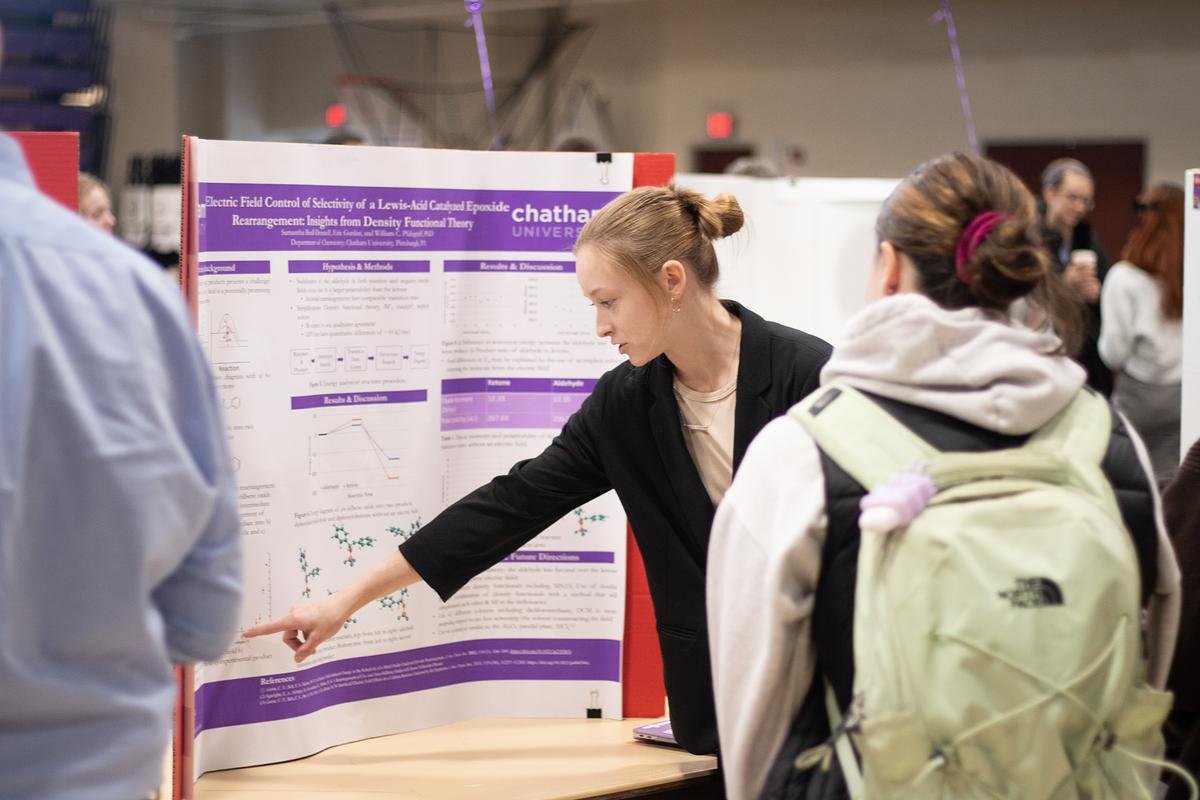

Samantha Beall-Dennell ’25 gestures to a poster explaining her research into the effects of electric fields on chemical reactions at Chatham University’s research day in 2023. (Liam Lyons)

There are some chemical reactions that make not one but multiple products. The useful parts come with the useless; the harmful bonded with the harmless. Even in a lab, that can’t be easily changed.

A group of undergraduate students at Chatham University are researching a way to change the conditions of a chemical reaction, using electric fields, to see how it may be possible to obtain only the desired products from a reaction.

Sam Beall-Dennell ’25 was awarded the Goldwater Scholarship as part of her computational research into the project. “Winning it has given me that confidence to continue full-steam ahead with what I’m doing,” Beall-Dennell said during an interview in the Jennie King Mellon Library in April.

Her research advisor, William Pfalzgraff, assistant professor of chemistry, is the Goldwater Representative at Chatham. He said Beall-Dennell was the first Chatham student to obtain the award, which was created by Congress in 1986 in honor of Senator Barry Goldwater. It’s positioned as the “preeminent undergraduate award of its type” in the fields of science, engineering, and mathematics.

Pfalzgraff used pharmaceuticals as an example of how this tool could potentially be used by real chemists. The chemical reactions to make common drugs, such as ibuprofen, result in a product that treats people’s headaches. However, these reactions also result in other products which have, in the case of ibuprofen, no effect.

Using electric fields may allow chemists to obtain only the “useful” products from a reaction, which would reduce waste and save resources by eliminating the need to purify or remove any unwanted substances.

Pfalzgraff noted that they are still in the proof-of-concept stage of this research, trying to see if their hypothesis around the electric field is feasible. It has the potential to be applied to many fields.

Beall-Dennell, who majors in biochemistry and mathematics, was brought into the fold by Pfalzgraff after she told him she was interested in getting into research. After familiarizing herself with the project, she started to run simulations on a computer to explain how and why the experiments using the electric field work. She also suggests how future experiments could be done.

Syba Ismail ’25, a chemistry major, is one of the students who handles the experimental side of the project. That work has included making electrodes, which meant she had to gear up and work in the clean room at the University of Pittsburgh.

“You have to bring different shoes whenever it’s winter and there’s salt on the road,” Ismail said. “You have to clean the bottoms of your shoes. You have little socks, like a hair mask, that you put over your feet. They offer these cloth gowns that you have to wear.”

“I really liked being able to go there,” she said. “It was an interesting experience to say I was making nanomaterials. I know that helped me with applications for other research programs.”

While Ismail worked in the lab, Beall-Dennell carried out the same types of experiments on a computer to see if they achieved similar results. To carry out these simulations more quickly, Beall-Dennell taught herself the coding language Python.

“All I have to do is type in a command, and it just does it for me now,” she explained. “I had no prior coding knowledge, and [Pfalzgraff] was like, ‘I think you’re up to the challenge.’ … I actually really enjoyed it.”

Pfalzgraff said their project is an example of the opportunities available at a university like Chatham, where professors can provide one-on-one mentorship to students.

“Research is hard, and you don’t know how to get into research when you’re starting out in college,” he said. “Having some really good mentoring is really valuable.”

Beall-Dennell agreed: “I wanted a small school, where my professors could get to know me.”

And, she said the tight-knit community at Chatham University has also allowed her to find peers with whom she shares similar interests in chemistry, lacrosse, and beyond.

“The people that are passionate about the same things as me are people that I know, and I can make a connection with [them],” she said. “These are real people I’m making a connection with, not just a face in the crowd.”

Learn more about the research opportunities available at Chatham University at chatham.edu.