The Smarter Lunchrooms Movement comes to Pittsburgh Public Schools

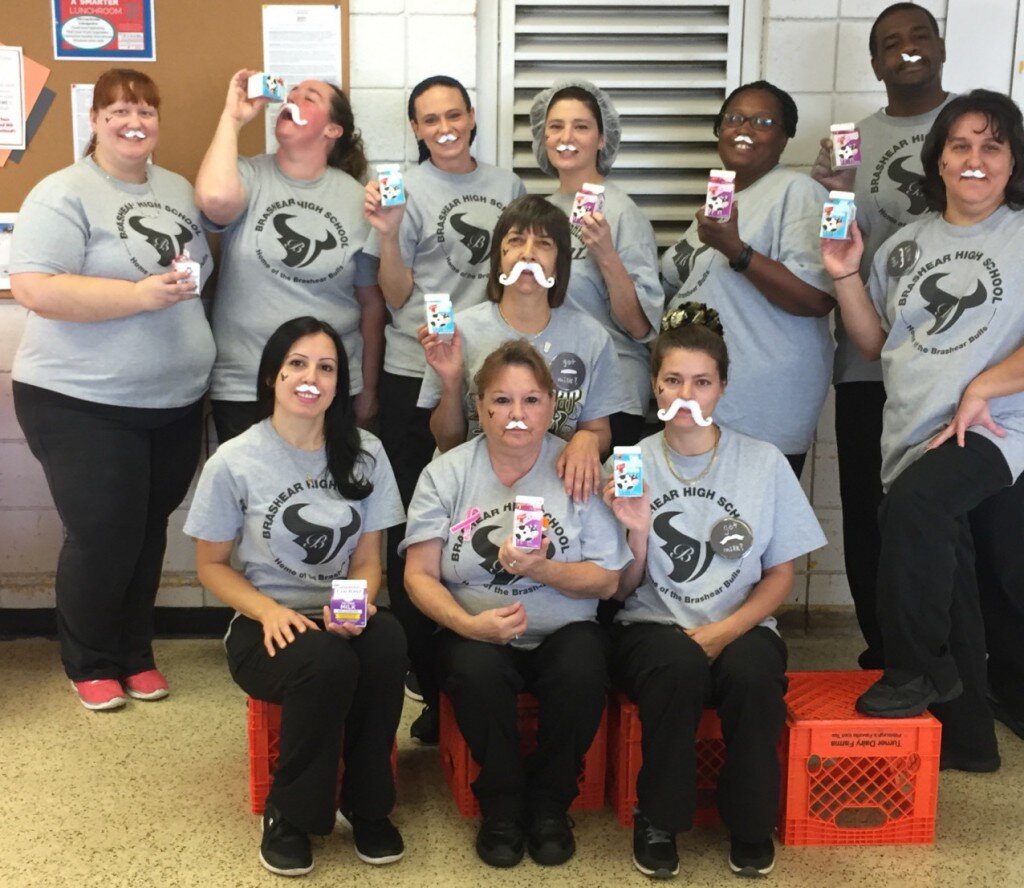

Brashear High School Food Service Employees are starting their day with the power of protein! Cafeteria Manager, Kathy Harris (center), uses the #milklife campaign to get kids to drink more unflavored milk at lunch.

Simple changes in the environment can lead to healthier lunchtime choices. That’s the thinking behind the Smarter Lunchrooms Movement (SLM), a program started in 2009 by researchers at the Cornell Center for Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition. In a study funded by Highmark, Chatham graduate student Dani Lyons, Master of Arts in Food Studies ’16 teamed up with food services dietician Elizabeth Henry to bring it to 19,000 children across all 56 elementary, middle, and high schools in the Pittsburgh Public Schools system in 2015. This work comprised Dani's Master's thesis, and her final report can be read here.

Questions of who has access to what kind of food play out in an interesting manner in public schools.” - Dani Lyons, MAFS '16

The Smarter Lunchrooms Movement borrows a concept from behavioral economics: hot-state vs. cold-state decision making. In cold-state decision making, we’re more likely to weigh pros and cons and consider long-term consequences of our actions. In contrast, hot-state decision-making favors the quickest, easiest, most immediately satisfying option. It tends to be the default setting in children, exacerbated during periods of time pressure and academic and social stress, like in a school lunchroom.

SLM aims to game hot-state decision making by making healthy choices more visible and more appealing. To that end, Dani and Elizabeth worked with local school food services staff to implement four initiatives, one per week for four consecutive weeks:

1. Menu boards

Large, wet-erase black whiteboards placed at the beginning of the lunch line let students know what’s available before they confronted it later in the line. This built-in pause offers an opportunity for them to consider what they might like to eat, lessening the chance that they’ll make a spur-of-the-moment decision. “Research suggests that if you prime students for a meal advertised to be delicious, students are more likely to eat the healthy food to take because they expect it to taste good,” says Dani.

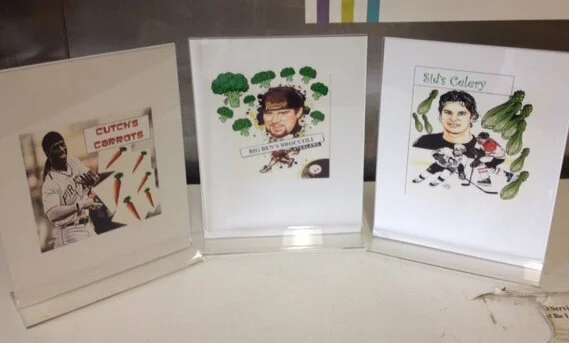

2. Cool names

Giving foods fun, memorable names can increase their appeal to students. Schools were given signs with photos and slogans advertising Game-Changing Green Beans, #BOSS Baked Beans, and Smoky Chipotle Bean Salsa. Some schools invited students to name foods themselves.

3. Putting white milk first

At least one-third of all milk in each cooler was white milk, and it was the first in each line or in the front of the cake. Lunchroom banners and posters advertised the “MilkLife” campaign.

4. Improving visibility of fruits and vegetables

Schools were given tablecloths, fruit bowls and “fruit chutes”—wire chutes that hold and dispense whole fruits—and other ways to emphasize fruits and vegetables in the cafeteria line were suggested.

Before the interventions, Dani conducted an 8-hour training session for PPS food service mangers and other staff members about the Smarter Lunchroom Movement, introducing them to the four interventions. There was also a one-hour follow-up training session.

Results

To assess the study’s efficacy, Dani interviewed ten food service managers, and the team gathered observational data pertaining to how well the lunchroom adhered to best practices at ten of the schools schools, and did before-and-after analyses of how much food from students’ plates was being thrown away, and of computerized food sales and ordering data.

Dani and Elizabeth found that in every area, scores increased from the baseline data to the follow-up data, by a minimum of 12.2% and at most, 38.6%. “Milk drinking increased,” says Dani, “as well as the proportion of white to flavored milk chosen. Vegetable choice increased, and we saw kids who chose more than one vegetable tended to eat them both.”

She points out that while they only collected follow-up data from 10 of the 57 schools, there’s reason to believe that the other schools would also have seen an average increase in all areas as well, since all schools received the same training, materials, and instruction for implementation.

Dani acknowledges the challenges that schools face in getting students to make good lunchtime selections. “Half of the schools don’t have a kitchen,” she says. “And they don’t use plastic trays, so students have to carry their food. That’s another obstacle—kindergartners can’t carry their lunch in their hands.”

Tips for parents who are trying to get their kids to eat more healthily at home? “Managing serving size is probably the most effective thing you can do,” says Dani. “We know it’s economical to buy in bulk, but then we find ourselves eating out of the package. So divide trail mix into individual servings and store them that way. Also, when we use smaller serving utensils and smaller plates, we serve ourselves less. The opposite holds true, too—if you want your kids to eat more salad, buy larger salad prongs.”

Among her favorite courses in the Food Studies program, Dani counts U.S. Agricultural Policy (“We learned the Farm Bill inside and out and took a trip to DC to meet with lobbyists, researchers, and other people involved in the politics of food and agriculture.”) and The Politics of Chocolate (“We focused on labor practices; marketing; parallels with tea and coffee; and human rights. And I got to design, produce, and market my own chocolate bar, which was delicious.”). After graduation, she plans to work in school food administration or in school food policy at local and state levels. “That may sound very boring to some people,” Dani laughs. “But I find it fascinating."

Learn more about the study at www.smarterlunchroompps.tumblr.com.